The Land Never Forgets: A Review of The Undertow

- TE RĀKAU

- Jan 24, 2017

- 6 min read

Updated: May 9, 2024

Adam Goodall for The Pantograph Punch | 25 January 2017

Adam Goodall reviews Te Rākau Theatre's The Undertow, a staggering eight-hour drama that holds New Zealand's colonial past, present and future up to the light.

We’re going to repair the land when the war’s over, the nurse says. We’re going to replace the mud with grass, the pillboxes with trees, the bombed-out houses with warm and welcome homes. We’ll change the land, put our suffering behind us.

Hamuera Kenning, a New Zealand soldier stuck in a Passchendaele purgatory, recognises her optimism. He’d like nothing more than to share it. “My country’s been trying to do that for years,” he tells her. “But the land never forgets.”

The land and its memories are always at the centre of Helen Pearse-Otene’s The Undertow, a four-part history of Wellington and New Zealand presented by her and Jim Moriarty’s storied company, Te Rākau Theatre.

This eight-hour history is woven in with the history of the Kenning whānau, tracking them from the circumstances of their taking the Kenning name in The Ragged to their final act of resistance against the capitalists thirsty for their kāinga in The Landeaters.

Over those eight hours, their land is loved, used, threatened, abused and ultimately stolen from them.

Te Rākau communes with that land under yellow and purple lights, diffused by fog, calling to life the ghosts of those four generations.

'towers of men and women creating seas and taniwha'

The commune begins in The Ragged with Manchester-born Samuel Kenning (Matthew Dussler). In 1840, Kenning comes to Te Miti, the papakāinga of aging chief Te Waipouri (Moriarty) and his hapu, to claim the land he’s bought from the New Zealand Company.

Quickly discovering that he’s been defrauded, Kenning first attempts to claim the foreshore as whenua taunaha then reluctantly accepts Te Waipouri’s hospitality, hospitality offered against the advice of his brash daughter-in-law Peata (Kimberley Skipper).

The wealthy Pākehā settlers at Port Nicholson want Te Miti, though, as does Governor Hobson, and the Governor’s sent his man Crippen (Zechariah Julius-Donnelly) to acquire it by any means necessary.

A sprawling but linear historical drama that moves along at an unhurried pace, The Ragged is the most conventional and also the most static of the four chapters. Moriarty and his choreographic team break up the scenes with immense and beautiful evocations of the natural forces in Owhiro Bay – towers of men and women creating seas and taniwha – but when it’s time to talk the performers move as if on rails, standing in straight lines, delivering dialogue in awkward direct address.

The direct address is made more awkward by performances that are lacking in range and depth. Moriarty and Skipper are strong, grounding the action Te Miti with compassion and the deep pain of personal tragedy, but Dussler bellows his way through most of the play and Jeremy Davis, playing Te Waipouri’s socialite son Tame, talks like a politician making a stump speech every time he’s facing the audience.

That’s one of the risks of presenting these plays in repertory: when you’re directing thirty performers who have to remember eight hours worth of staging and dialogue, it’s understandable that you’d want to make it simple for them.

Moriarty pushes against that impulse more and more in the subsequent chapters. Dog & Bone bursts onto stage with a hilarious, unapologetically heavy-handed opening in which a prim colonial dog show is invaded by Ngāti Irawaru and their “unruly”, “independent” kuri.

Pearse-Otene then takes us to the Kenning Homestead, 1869, overlooking Owhiro Bay. Tāiki Kenning (Reuben Butler) lives in the Homestead with his Pākehā wife Hannah-May (Greer Phillips) and her father, the curmudgeonly former politician William Beamish (Ralph Johnson).

Tāiki, a military scout for Her Majesty, has been called to Taranaki for one last shot at Tītokowaru; his brother, Kurītea (Manuel Solomon), has thrown in with Ngāti Ruanui in order to protect Taranaki from the ‘landeaters’. Receiving a chilling prophecy, Kurītea returns to Te Miti to talk his brother out of marching to his certain death.

Microcosm of damage caused by colonisation and greed

Dog & Bone hides the passage of time in theatrical ellipses, blurring that onward march as the Kenning Homestead subconsciously prepares itself for tragedy. Public Works messes with our sense of time even further, the past and the future bleeding into 1917 Passchendaele. There, cousins Will Meier (Butler) and Hamuera Kenning (Solomon) live in limbo, waiting for Allied relief troops in a pillbox they’ve miraculously taken from the Germans. As they watch the empty battlefield, the scars of their service and their history deepening with each passing night, they’re visited by family, ancestors, descendants yet to be born. They’re also visited by Fleur (Phillips), a Belgian nurse who knows more than she’s letting on.

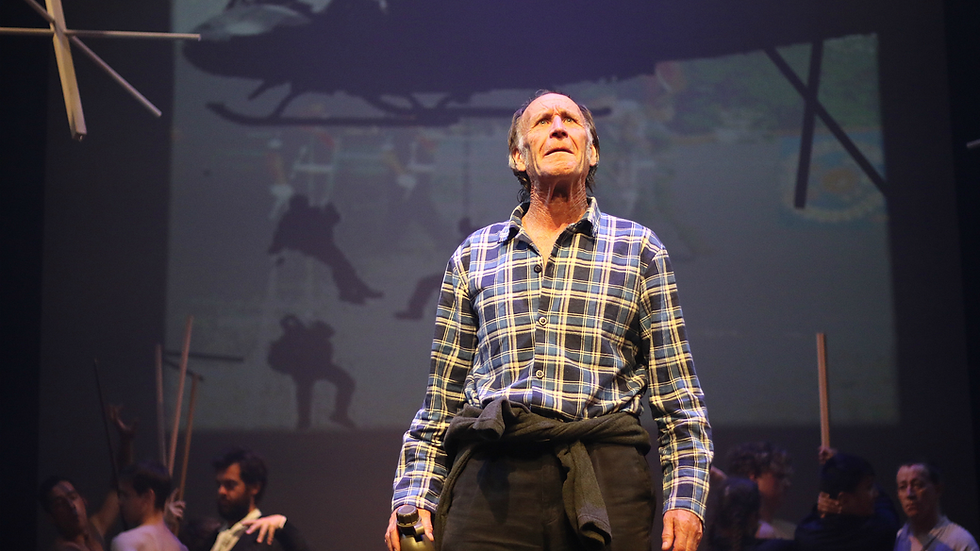

Those scars are opened in The Landeaters, set in “the day after tomorrow.” Ghosts swirl around the stage, beautiful, threatening, ever-present reminders of the whakapapa that Vietnam veteran Harry Kenning (Johnson) is trying to defend from Wayne Tinkerman (Dussler), a property developer who wants to build a bougie retirement village where Te Miti once stood.

The Kenning Homestead torn down, Harry starts living under a 200-year old willow tree planted on the property by Hannah-May in Dog & Bone. But when Tinkerman falls down a hole into Harry’s makeshift underground home, Harry enlists him in finding a memory long lost underground – if they can fight off Whero, the Eater of Souls, first.

Across all four chapters, the Kennings’ experience acts as a microcosm of the damage that colonisation, colonialism and greed has inflicted on New Zealand.

Impeccably researched, Pearse-Otene’s script is an incredibly sophisticated and galvanising presentation of two hundred years of exploitation and bigotry inflicted by the ‘respectable’, ‘civilised’ state against Māori and the poor.

Pākehā and Māori are frequently in close quarters and there’s plenty of individual bigotry and racism on display, whether it’s the Port Nicholson settlers declaring that New Zealand is “wasted on the Māori” or Beamish treating his son-in-law like one of the ‘good ones’, “not like those savages”.

But The Undertow is also a comprehensive and unwavering survey of the ways that colonising forces built and continue to build laws that legitimise their theft, their abuse, their greed.

Hobson’s man on the ground, Crippin, pals around with the openly fraudulent company man Spooner; Pākehā soldiers returning from Europe are offered a townhouse and land, while Māori soldiers are offered nothing; Harry’s community fights against the retirement village, but they’re knocked back by every court and tribunal in the land.

Busting the myth of equality and fairness

In each play, this noxious institutional racism creates obstacle after obstacle, pushing Māori back down every time they get their heads above water. Across all four plays over eight hours, it’s not just noxious, it’s suffocating.

In its totality, The Undertow is a portrait of the unrelenting racism and rapacious capitalism on which the New Zealand Project is built. It busts the million myths that New Zealand tells itself about its sense of equality and fairness, and it’s remarkable that it does so with both anger and empathy.

It’s also remarkable that Pearse-Otene manages to do this consistently over eight hours. Aside from the occasional false note (melodramatically ending The Ragged with Johnny Cash’s ‘Hurt’, for example), she and Moriarty keep this heart-wrenching history alive, vibrant and oddly funny.

Pearse-Otene mines the Kenning’s domestic lives for small joys and warm humour, and Moriarty punctuates scenes with waiata, kapa haka and thrilling, stage-consuming ensemble work.

It’s all there in the way that the ghosts of the land encircle Harry in The Landeaters, swelling and contracting around him, his ancestors lifting him up and following his every move; it’s there in Dog & Bone’s Tree, a sapling played by two pre-teen girls that transforms into a towering girl-willow, swaying with the storm as it reminds Hannah-May of the story it once told her, of the death tied up in the land.

That sense of inescapable tragedy is what elevates Dog & Bone above the rest of a strong quartet. Tāiki, the naive conservative, helps the Pākehā because they claim to want peace; Kurītea sees the imperial Government’s deception for what it is, and implores Tāiki to stay behind, not just for himself for his people.

Pearse-Otene complicates the classic war story imagery of brothers divided, using it as a vehicle for exploring the painful, centuries-old divide between conservative and radical Māori and the way that divide was exploited by colonial forces.

With a strong grip on the escalating melodrama (and a startling, powerful performance from Solomon that switches between furious and mournful on a dime), Pearse-Otene and Moriarty steer Dog & Bone to a grand, devastating finale that single-handedly justifies the scope of this project.

The Undertow doesn't always run smooth, but that's almost inevitable given its eight-hour run-time, 30-strong cast and two centuries of history to tell. It’s hard to overstate how necessary this work is, though.

Te Rākau have made a spectacle that’s vital and unlike anything being made in Wellington, and perhaps in New Zealand, today.

It’s audacious, often beautiful and a welcome antidote to the state-of-the-nation plays that too often avoid wrangling with the colonial pollution of New Zealand's history.

It’s an uncompromising communication of the poison that runs deep in our land, a powerful challenge to remember a history that never stopped living, and a stirring invitation for us to come together, to connect, and to start healing.

This review was originally published in The Pantograph Punch. Visit the website for more.

Comments